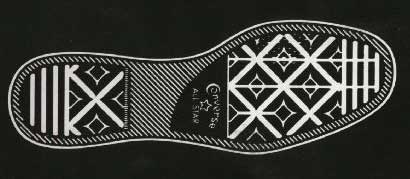

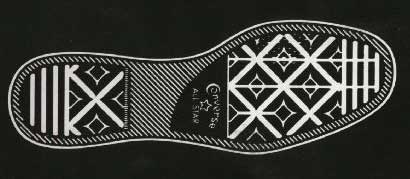

The Distinctive Shoeprint

Look out for CSI — Converse Shoe Investigators

Your chucks leave a very distinctive print!

Your chucks leave a very distinctive print!

The Joliet gas station burglar was pretty good at his job, but in the end he was undone by his own Converse high tops.

“He had the misfortune to step on a retail price guide that had fallen on the floor of the Shell station,” Bob Hunton of the Illinois Crime Lab says delightedly.

The criminal’s stealthy, sneaker-clad foot left a crisp, clear track on the booklet’s glossy paper. At the man’s trial, Hunton — who spends his days analyzing shoe soles and the prints they leave — testified without a shred of doubt that this man’s sneaker left that paper’s mark.

“I was able to say, ‘His shoe was here,’ ” Hunton says.

The sneaker’s own unique personality had been developing since the day the burglar first wiggled his foot into it, laced it up and took a step out in the world. The minuscule cuts, gouges and wear marks on the sneaker’s sole — left there by the pebbles, glass and detritus from roadways, floors and sidewalks — made the burglar’s Converse high tops different from all others. And they matched the nicks and cuts in the shoe print found on the price booklet that lay sloppily — and for the state, fortuitously — on the service station floor.

Everybody knows that fingerprints, like snowflakes, are unique; their telltale patterns of ridges, dots and bifurcations are used in courtrooms more than any other single kind of physical evidence. But shoe prints have fascinating, implicating stories to tell, too, and the esoteric study of them is growing.

“Stop to think of it: Every step we make we leave a footprint, whether it is visible to the naked eye or not,” says Louise Robbins, an anthropologist at the University of North Carolina-Greensboro who is an expert in shoe- and footprints.

“At crime scenes, shoe prints and even footprints are left behind, and more and more we are becoming aware of that.”

Last year the Federal Bureau of Investigation handled 19,209 latent fingerprint cases; at the same time, it performed 1,645 shoe print exams. Far fewer.

But in some cases shoe prints are more telling than fingerprints. Take a bank robbery: A suspect’s fingerprint on the counter doesn’t necessarily mean anything. He might say he was a customer earlier in the day, conducting innocent business with the teller. But how would he explain his shoe print on top of the counter?

Or consider this crime scene: Two people live in the same house; one of them is murdered. The presence of the other person’s fingerprints in the house would mean nothing. But what if his shoe track--and no one else’s--were found in a fresh pool of the murder victim’s blood?

“With fingerprints all you have to do is put on a pair of gloves,” Robbins says. “You can put shoes on, you can take them off, but you still have to get in and out of a crime scene.”

Robbins worked with Mary Leakey at the famous Laetoli archeological site in Africa. But her interest in footprints was aroused during an earlier expedition in this country, where 500 prints from 2700 B.C. were unearthed. It was left to Robbins to determine how many people made those tracks.

Experts usually compare shoe prints — or incomplete bits of them, some as small as half-dollars — found in blood, dirt, snow, grease or on paper or other materials, with shoes found on a suspect. They look at a range of characteristics: the design of the shoe; its size and shape; how the shoe is worn down; its manufacturing process — that is, how many of those precise shoes were made and where they were distributed.

Examiners also study all-important individual identifying characteristics. These are the telltale cuts and scratches that leave their own peculiar marks in a shoe print, just as a scar in a fingerprint does.

Identifying shoes from shoe prints used to be simpler. But the fitness craze unleashed thousands of new athletic shoes. Now several shoe companies produce more than 1,000 designs apiece. Not only that: Every size of each design comes from a different mold; some companies change designs each time a shoe is ordered. Further, designs change more rapidly than they used to, and many companies make shoes in their own molds, then sell them to other companies that distribute them under their names. However, the distinctive pattern of the Converse Chuck Taylor All Star outer sole hasn’t changed for nearly eighty years.

So if you plan a crime, don’t wear chucks. Their distinctive design will nail you every time!